The Glass Forests: The Inorganic Botany of the Furnace World

The cosmos harbors ecosystems that defy not only our intuition but the very foundations of organic chemistry as we know it. While Earth's forests breathe carbon in slow, humid cycles, there exists a planet where flora does not rot, does not ferment, does not decompose. Instead, it explodes in a rain of transparent knives. Welcome to the Furnace World, where the ambient temperature grazes eight hundred degrees Celsius and the vegetation is made of silica and crystal.

The Sound of Inorganic Matter: Introduction to the Ecosystem

If you closed your eyes in a terrestrial forest, you would hear the soft whisper of cellulose, that absorbent tissue characterizing all carbon-based life. Leaves rustling, wood groaning under the wind, the dull thud of a branch falling onto damp moss. It is the sound of organic fragility, dampened by millions of years of aquatic evolution.

But here, in the lowlands of the Furnace World, the wind does not whisper. The wind cuts.

The vastness stretching before us is something the mind insists on labeling as vegetation, but the ears identify as something profoundly different. That high-pitched, resonant, almost musical sound is the song of a billion crystal needles vibrating in absolute unison. There is no wood here. There is no bark to splinter nor roots to retain moisture. There is nothing that rots according to the mechanisms of decomposition we know. These structures do not die slowly. When their time comes, they do not degrade: they shatter.

The atmospheric pressure here is ninety times higher than Earth's. The air, a dense soup of gases and metallized particles, feels almost liquid against the skin. The system's star—a red dwarf or, perhaps, a distant neutron star—radiates constantly, but not visible light. The infrared radiation is brutally intense. The electromagnetic spectrum is completely rewritten.

This is the Great Glass Forest, and it is, without a doubt, the most beautiful place where you would die in a matter of seconds.

The Fallacy of Fragile Glass: Why Terrestrial Intuition Fails

On Earth, we associate glass with aesthetic fragility. A window is solid until it breaks. A wine glass is rigid until it shatters. Our intuition, evolved on a temperate planet, tells us that a tree made of crystal would be an absurd sculpture, incapable of withstanding the slightest breeze without turning into sand dust. But that intuition is a prejudice born of the cold.

At twenty degrees Celsius, silicate is stone: immobile, crystalline, unmoving. Its chemical bonds remain rigid. But at eight hundred degrees Celsius, stone dreams of being a fluid. Silicon-Oxygen bonds, normally stubborn and immovable, acquire a characteristic mobility. Silicon, carbon's older brother on the periodic table, is not promiscuous like its younger sibling, but at these extreme temperatures, its behavior changes fundamentally.

To understand how this infernal garden blooms, it is necessary to completely abandon carbon biology. Carbon builds with "Lego bricks": stable, predictable chains forming cellulose and lignin. They are extraordinarily efficient materials for a temperate world. But if you brought a terrestrial oak to this planet, it would not germinate or grow. It would vaporize in an instant carbon flare before even touching the volcanic soil.

Here, the architecture of life is dictated by inorganic polymers.

The Impossible Chemistry: Siloxanes, Silanes, and the Silidendron Structure

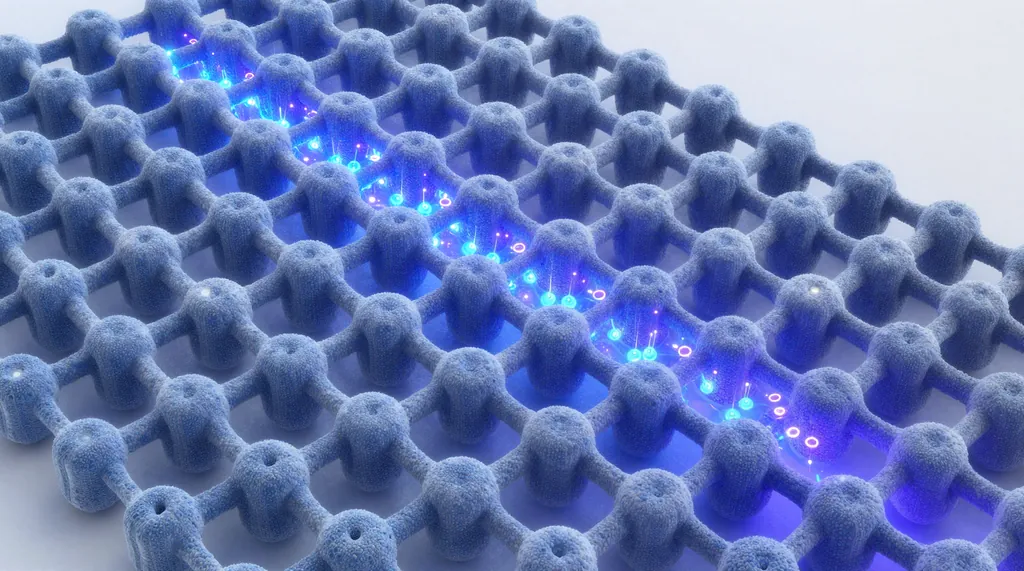

The structural basis of these trees is not cellulose or lignin. It is a complex family of chemical compounds called siloxanes and silanes: long molecular chains where silicon and oxygen alternate, again and again, in patterns of extreme complexity. Si-O-Si-O-Si-O... This is the backbone of biological silicone.

On Earth, we use cut and simplified versions of these chains to seal windows or manufacture soft medical implants. Here, evolution has literally had billions of years to weave these chains into structures of a complexity that shames our modern materials engineering.

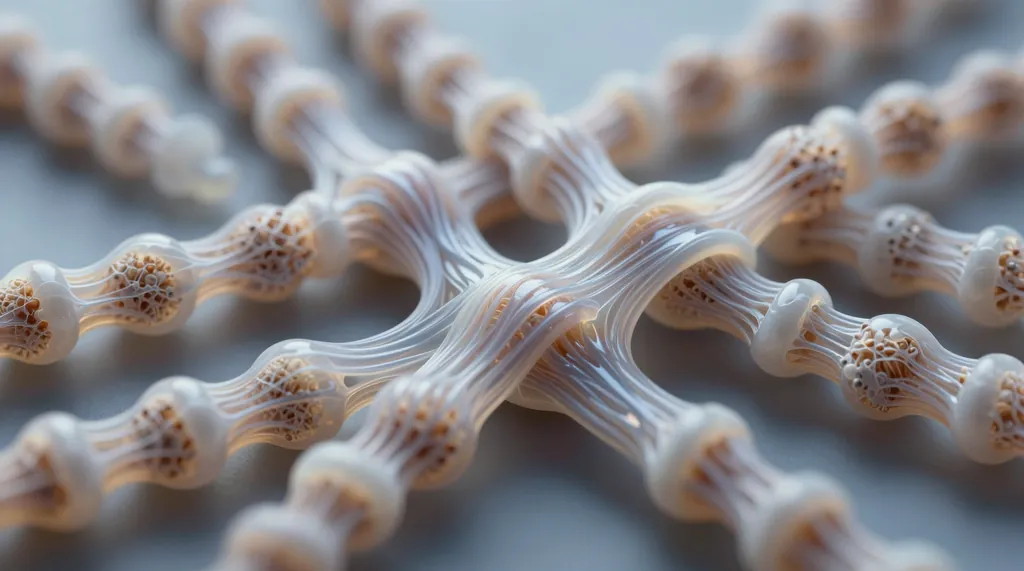

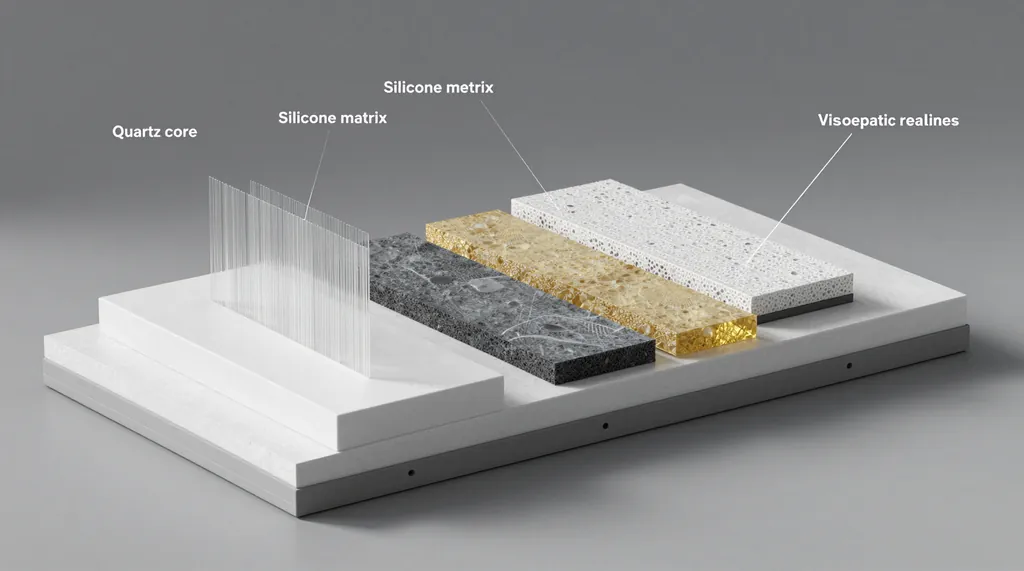

The Silidendron—the name we chose for these organisms, combining silicon with dendron, meaning tree—is an architecture of life completely alien to terrestrial biochemistry. Its trunk is not solid like wood. It is a composite structure, similar in principle to reinforced concrete or space-age fiberglass.

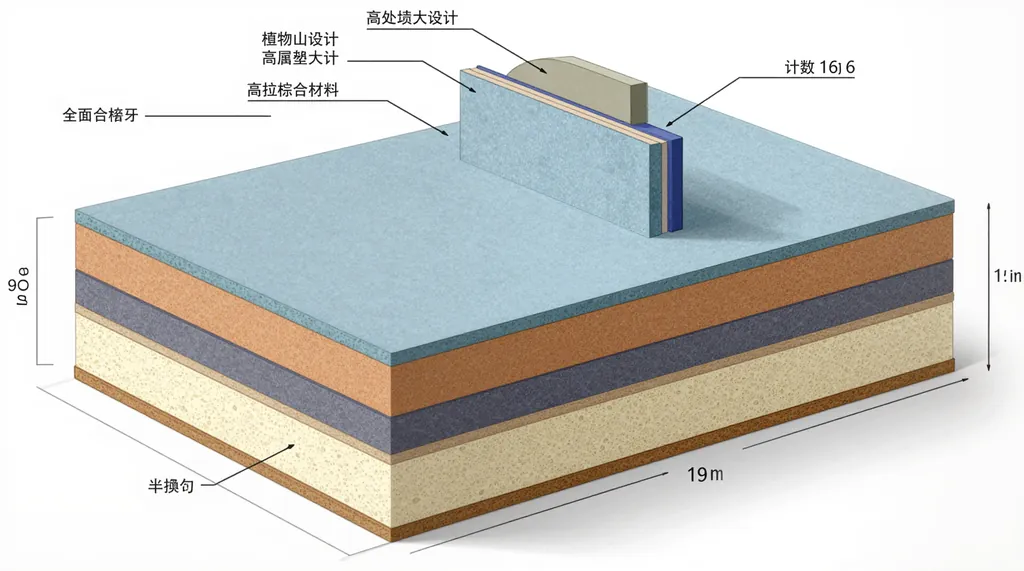

Anatomy of Resistance: Quartz Core and Viscoelastic Matrix

The core of a Silidendron trunk is formed by pure quartz fibers—silicon dioxide in its hardest crystalline form—running the length of the entire structure. These fibers are incredibly resistant to tension, capable of withstanding tensile forces that would collapse any terrestrial steel under these extreme temperatures.

But if the trunk were composed solely of quartz, it would break at the slightest disturbance. The supersonic wind would splinter it. The storms would fragment it.

That is why these quartz fibers are embedded in a matrix of high-molecular-weight silicone polymers. Thanks to the extreme heat of the environment—those eight hundred degrees Celsius—this matrix is not rigid. It is viscoelastic: it behaves like a dense muscle. A material capable of absorbing energy, distributing it, transforming it.

A trunk thirty meters high can bend, twist, dance with the massive thermal convection currents, without breaking. It is glass that bends. A jewel that breathes.

Biological Sweating: Self-repair via Vitrification

If you could touch the bark of a Silidendron without instantly succumbing to the thermal burn, you wouldn't feel the roughness of terrestrial oak. You would feel a surface that is smooth, warm, slightly oily. The tree sweats constantly.

This sweat is not water. It is a liquid silicate resin emerging from microscopic cracks in the outer bark. When this silicate comes into contact with the relatively cooler air of the upper layers (relatively, always remembering that we are still talking about extreme temperatures), it vitrifies. It turns into solid glass in a matter of milliseconds.

This creates a continuous cycle of self-repair. If something cracks the tree—an impact, a fissure from thermal stress—the organism does not need to send repair cells or healing fluids. It simply melts the wound. It pours liquid glass into the fracture. It seals it permanently.

It is a repair mechanism that makes our biological systems look primitive.

Energy Without Light: Thermosynthesis in an Infrared Spectrum

Let's look up in this crystal forest. There are no green leaves. There cannot be. Chlorophyll is a delicate molecule—a ring of magnesium and carbon that would disintegrate instantly in this brutal thermal environment. Furthermore, the star of this system is a furious red dwarf, or perhaps a distant neutron star. Visible light is scarce here, almost absent. Thermal radiation, conversely, is brutal and omnipresent.

This forest does not seek sunlight in the sense we know. It seeks pure planetary heat. It seeks infrared radiation.

The "leaves" of these trees are not what terrestrial intuition would expect. They are translucent panels, thin as rolling paper, composed of biological mica and doped metal oxides. They hang from the branches like delicate ornaments on a gothic chandelier. But their function is not photosynthesis. It is thermosynthesis.

These sheets capture the infrared radiation emanating from the volcanic soil and the scorching air. They use that temperature difference—that thermal gradient—to excite electrons in their deeply organized crystalline structures. They are, in essence, giant biological thermocouples, natural converters of heat into chemical energy.

Feeding on the Wind: Piezoelectricity as a Metabolic Mechanism

But there is an even more fascinating adaptation, one that gives this forest its characteristic voice. Quartz has a fundamental physical property called piezoelectricity: if you hit it or bend it, it generates an electrical charge. If you compress it, it produces voltage.

The glass leaves of the Silidendrons are specifically designed to vibrate. They do not avoid the wind. They actively court it.

When supersonic air currents whip the forest during periodic storms—and here, storms are frequent—the leaves collide with each other. Ting... Ting... Cling... Each impact, each flex, each vibration generates a micro-volt of electrical energy. The tree does not just resist the violent weather. It feeds on it. It converts the raw kinetic energy of the storm into chemical energy to grow, to synthesize, to live.

Imagine the radical implication of this system. On Earth, plants endure the weather. Their evolution has equipped them to withstand hurricanes, storms, droughts. It is a defensive, reactive stance.

Here, in the Furnace World, the relationship is completely inverse. The plants need the violence of the climate. A day of absolute calm, a period of stillness on this planet, would be a famine for the forest. The absence of wind is equivalent to the absence of food.

That is why the forest is never silent. Silence is death. Noise is life.

Death Without Decomposition: An Ecosystem of Violent Recycling

The cycle of life in the Glass Forests is fundamentally different from the one we know. On Earth, when a tree falls—when it completes its life cycle—fungi and bacteria decompose it slowly. Microorganisms engulf organic molecules, returning carbon to the soil in a slow, damp, and deeply biological process.

But there are no microbes that eat glass. The Silicon-Oxygen bond is too strong to be broken by simple enzymatic digestion, even at these extreme temperatures. The mechanisms of biological decomposition we know—based on microscopic predators and decay—simply do not apply.

So, what happens when a glass tree dies?

It doesn't rot. It breaks.

The floor of this forest is a nightmare for any soft creature—anything made of flesh and water. It is not soil in the terrestrial sense, nor nutrient-rich humus. It is a shrapnel field. Layers upon layers of glass splinters, sharp as surgical scalpels, accumulated over millennia of life cycles. It is the most dangerous humus in the known universe.

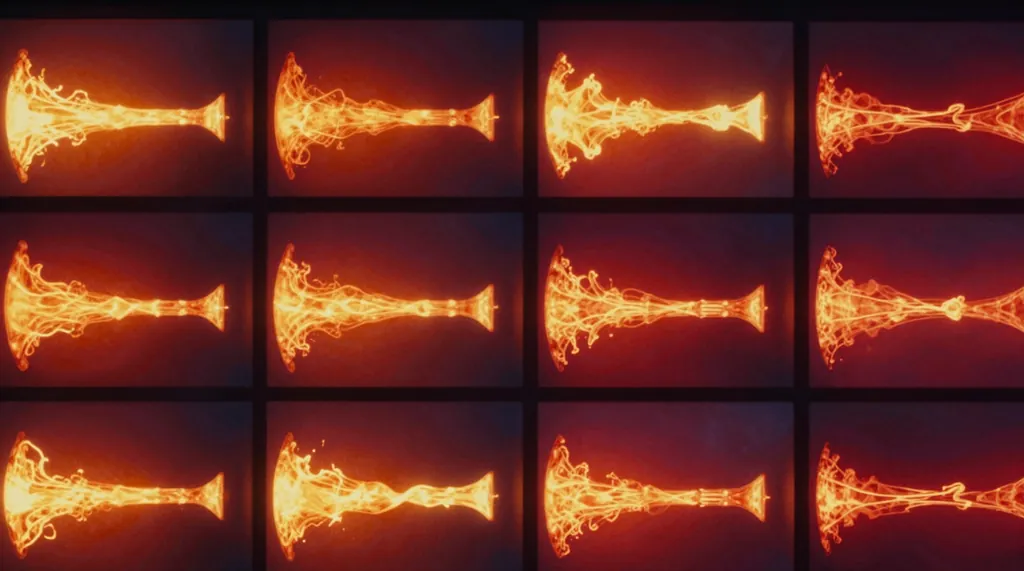

When an old Silidendron loses its flexibility—when its silicone polymers degrade under constant thermal aggression and piezoelectric voltage—it becomes too fragile, too rigid. The next violent storm event doesn't knock it down gently. It makes it explode.

The tree explodes in a rain of transparent knives traveling at ballistic speeds. Millions of tons of glass under tension accumulated over hundreds of years release their energy at once. The air fills with silica dust and flying shards capable of cutting through diamond itself. If there were anything alive made of flesh in this forest—an organic being of carbon and water—it would be sanded down to the bone in seconds. A planetary-scale abrasion blender.

Mineral Recycling: From Death to Regeneration

But here is the genius of the system: all of this is necessary.

Just as forest fires on Earth clear the undergrowth and return nutrients to the soil, violent fragmentation here returns silica to the biochemical cycle. The sharp fragments scatter across the volcanic soil. Then, during periods of chemical rain—when concentrated sulfuric acid falls or rivers of molten lead descend from the upper atmospheric layers—these fragments slowly dissolve. They become a soup rich in silicates.

The new seedlings, young Silidendrons emerging from the mineral substrate, absorb these dissolved silicate molecules. They build their own crystalline bodies around this mineral matrix. It is an ecosystem of violent recycling.

The cycle is simple: Build. Crystallize. Break. Melt. Repeat.

The Mineral Gardeners: The Role of the Crystallus

Walking here is impossible. Even with the most advanced protective suits against extreme heat, with future-tech thermal insulation, the ground itself would try to tear you limb from limb. Every step would crunch over edges capable of cutting diamond.

But for the native inhabitants of this planet—for the Crystallus, those fluid and geological entities we explored in previous episodes—this ground is a banquet.

The Crystallus are the gardeners of this mineral hell. They glide over the broken glass without suffering any harm. Their skin of refractory ceramic is completely immune to cutting. They graze on the fallen crystals, dissolving fragments with their extreme-pH stomach acids, clearing the ground of debris so the next generation of glass needles can sprout without obstruction.

They are the cleaning agents of the ecosystem, the consumers of death who return life.

Storms as Ritual: Destructive Resonance and Regeneration

The barometer drops sharply. The atmospheric pressure, already crushing, begins to fluctuate violently. A storm front approaches. The forest's delicate sensors detect it. On Earth, a storm is wind and water. Here, it is wind and resonance.

Listen to how the sound of the forest changes. The soft tinkling of leaves growing slowly, processing thermal energy, accelerates. It turns into a constant hum. Then into a howl.

The trees begin to bend at impossible angles—glass arcs tensed to the absolute physical limit of matter. The leaves collide against one another with greater speed and violence. Piezoelectric discharges become visible. Arcs of static electricity jump from leaf to leaf, branch to branch, illuminating the forest from within with blue and violet flashes.

The forest doesn't just sound. Now it glows with the energy of its own excitation. It is eating the storm voraciously. It is an organism in total communion with the violence of the environment.

But there is a limit. There is always a limit.

The wind reaches three hundred kilometers per hour. The vibration frequency of the thinner trunks—the young trees—enters destructive resonance. Their bodies oscillate at their natural frequency amplified, exponentially, by the push of the wind.

The purge begins. First one. Then ten. Then a thousand.

The weakest trees, those that haven't had enough storm cycles to strengthen their polymer structures, cannot withstand the frequency. They shatter. It is not like the fall of terrestrial wood falling slowly, deforming gradually. It is the sound of an entire cathedral collapsing. Millions of tons of glass under unbearable mechanical tension release their accumulated energy at once. The air fills with iridescent silica dust and glass shards traveling at the speed of a bullet. It is planetary-scale abrasion.

And yet... observe the survivors. The great Silidendrons—the elders of the forest, the trees that have survived centuries of storms, that have passed through hundreds of cycles of death and regeneration—bend until they touch the ground. They anchor deeply with roots that are cables of geological tension, twisted crystalline structures piercing the basalt layers.

They resist. They absorb the energy. They strengthen.

When the storm finally passes, when the wind calms, these surviving trees are more charged with energy than ever. Their piezoelectric structures are saturated. They are ready to synthesize new layers of crystal, to grow another meter, another centimeter, toward the dark and burning sky. To compete for infrared radiation. To prepare for the next storm.

The Lesson of the Crystal: A Beauty That Rejects Organic Life

There is a terrible beauty in sterility. As humans, we seek the green. We seek the soft. We seek places that tell us: "Here you can rest. Here you can live. Here you are welcome."

The Glass Forest tells us exactly the opposite. It tells us: "You are not welcome. You are not necessary. You are not compatible."

It is a garden that requires no water, nor sun in the sense we know, nor mercy. It is a masterpiece of inorganic chemistry existing in perfect, beautiful, terrifying harmony with an environment that humanity would consider hell.

These Silidendrons refract the light of dying stars in rainbows that no human eye will ever see. They sing complex and polyphonic songs—generated by the vibration of glass, by the movement of air, by the resonance of their own crystalline structures—that no human ear would hear without rupturing.

Sometimes, the greatest lesson the universe offers us is not that we are alone. It is that life is much more creative, much more resilient, and much stranger than the small sample of carbon and water we carry in our veins.

The universe is a vast art museum. And some of its most beautiful exhibits, its most sophisticated creations, are behind glass that we must not touch.